I published two UFO books in 2024. One was a 400 page contemporary history of government action on UFOs covering just one year, 2023. The other was a 170 page short story collection on the theme of UFO disclosure, The UFO Chronicles: District of Columbia.

The genesis of both of these was 2018 when I lost my comfortable assumption that UFOs were nothing more than modern myth and I became rabidly curious about what they might be instead. I began reading everything I could, and in 2021 I started writing articles, which evolved into the Disclosure Yearbook Series. Because my first love is fiction writing, I would tuck away character ideas, plot devices, and themes that popped into my head, a habit I’ve had since third grade. I wrote the short stories in 2021, 2022, and 2023, years that not only tracked my own journey of UFO discovery but the very public UFO journey of large swaths of our citizenry and our government, including the US Congress, the Pentagon, and NASA.

The journey of UFO discovery is bumpy. The path is rocky and narrow. There are many wrong turns, blind alleys, and sinkholes, and sometimes whole sections of trail break away beneath your feet. There is no clear destination and no map. There are guides, people who have been on the journey a lot longer than you have, but it’s often very hard to discern the ones who are useful from the ones who have completely lost all their bearings, from the ones who are just trying to sell you a map and a compass they mass produce in their basement. The reason for all this has to do with the fact that UFOs have always been barred from entry into the logbooks of accepted history, professional science, and established fact. That is not to say there are no UFO history and science books, or records, accounts, data sets, and archives--there are many, good and important ones too. I would not be writing this if I did not find much of the eyewitness testimony and prior government accounts credible and compelling. But they all exist outside of the establishment, closed off from mainstream thought. Anyone setting out to answer the UFO question for themselves has to slog through an enormous pile of mostly uncurated source material, some of which is pure bunk, and all of it is hard to believe. How is it helpful, you ask, to bring fiction into this challenging information space?

Having produced both types of UFO source material, let me tell you what I’ve learned.

A safe, bounded space for speculation

Speculating about UFOs is part of the fun, but in trying to understand UFOs, it can be dangerous. Speculation is so rife in this field because no one (yes, no one) has any idea what UFOs actually are. In one sense, speculation is all we can really do. The trouble is when you jump into a speculative rabbit hole, there is no bottom, you just keep going down. Trying to get inside the head of the UFO occupants (whatever they may be, if they even have heads, etc.) almost always leads to bad theory. Most of the resulting theories simply project onto the aliens (or whatever) human sensibilities and experiences, which also usually conform to the theorist’s preferred social and political views--as humans, that’s all we can really do as well.

In my historical and archivist writing, I decided early on to basically ignore the UFO and its occupant (if they have them, etc.), and focus on the impressions the UFO leaves on the witnesses, on the actions officials take as the result of a sighting. You can tell an awful lot about the phenomenon this way, and you are protected from starting down a line of thinking that will eventually seduce you into the belief that you have finally found The Answer. We are very far from answers.

But the only way to get to an answer is to start asking a bunch of speculative questions. As I said above, speculation is part of the fun, so we’re going to do it no matter what. Fiction allows a safe, bounded space to have this fun, and to use speculation to expand our thinking, but where the stakes are low enough that the speculation does not run ahead of the evidence and loom too large in our understanding of the phenomenon.

In The UFO Chronicles: District of Columbia, each story has a UFO and an alien being, but each one is different, acting on different motivations, depending on the story. Maybe the aliens have been trying to get our attention all along using standard first contact protocols, but humans are a uniquely stubborn and inward-looking species so the visitors are forced to take a page from our movies and literally land on the White House lawn. Or maybe the aliens are playing the long game and have been engaging in a delicate conversation with our collective consciousness. Maybe they don’t care what we think. Maybe they are not aliens at all, but humans from the future. Fiction allows you to dip your toes in a speculative thought experiment, or even plunge all the way in. But you get to turn the page on this idea or that. You eventually close the book and put it away. It doesn't ask any more from you than a simple laudation of ‘That was interesting.’

In 2022, mainstream investigative journalist Ross Coulthart turned the focus of much of his professional work onto UFOs. He wrote a book, filed TV news reports, and became a regular guest in the UFO podcast circuit, eventually starting his own UFO podcast. At one point he relayed that some of his sources were telling him the following explanation for UFOs: UFOs are advanced human technology from the future; they have traveled back in time to avert some kind of global cataclysm; the UFO gatekeepers in our current government are aware of this and it is actually the reason for strict secrecy; if disclosure were to happen, it would upset the future humans’ plans and bring about the cataclysm. In the brief period when Coulthart popularized this theory, a sitting congressman said he had become convinced from the same or similar sources that UFOs were piloted by humans from the future. This speculative bubble soon passed, though it’s still one of the major theories.

As a fiction writer, that is an irresistible story idea. But it is also crazy-making to be whipsawed from one wild idea to the next. It is perhaps why UFO interest has such a high burnout rate. It’s also clearly someone else’s fiction masquerading as The Answer. I say this because it’s highly unlikely that these sources had access to all the evidence that would make every piece of that time-travel story a reality. They took a few established facts (say, confirmed UFO sightings over nuclear missile sites) and connected the dots a certain way. Or they are pure fabulists. Or maybe it actually is more likely that humans are alone in this corner of the universe, and the physics of time travel is easier than warp drive, and deep government insiders chose to burble that fact to a reporter and a two-term congressman. What do I know about how the space-time continuum really works? Not very much. Again, crazy-making.

Keep the speculation to a minimum in the fact-based real world, but let it fly in fiction. Just be sure to put the book back on the shelf.

Grounded in Real Life

UFO acceptance, when it happens to you, can be an all-consuming proposition. A switch gets flipped and UFOs become the most important thing in the world. How could they not be? Not only are we not alone in the universe (or the multiverse, or the space-time continuum, etc.), they have been on this earth for a long time, a fact that has been kept an enormous secret by our own government. You think this is all anyone should care about. And when some piece of the mystery does pop into the news, you can’t understand why it’s not an earth-shattering breaking news event earning wall-to-wall coverage. You lose sight of the wider world and the complexities of our social dynamics. This in turn makes it harder to foresee how disclosure, which means society-wide UFO acceptance, will interact with, well, everything else you don’t think is as important.

Fiction can and should weave you back into the social fabric with the rest of your fellow human beings. Writing my own UFO fiction, I came to some surprising conclusions. Fiction, because of its breadth, nuance and humanism, can tap into certain truths that we might otherwise miss.

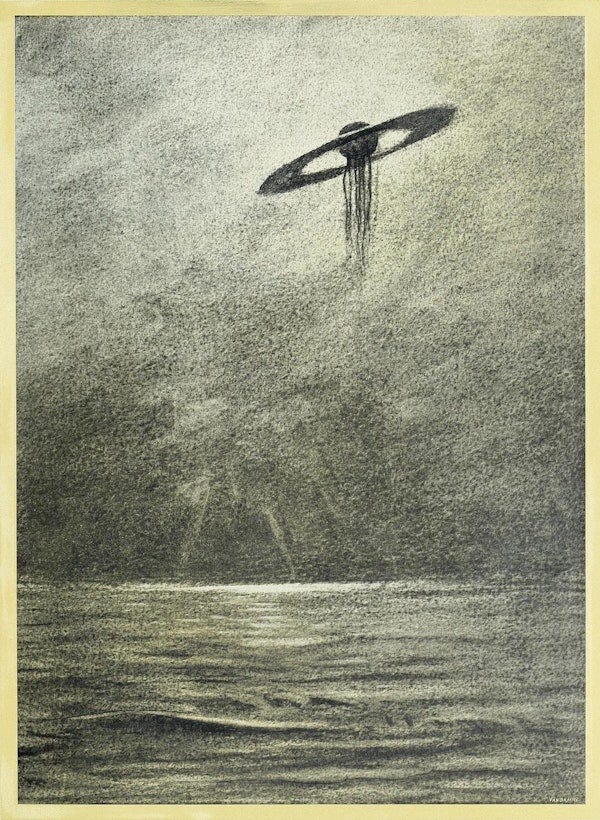

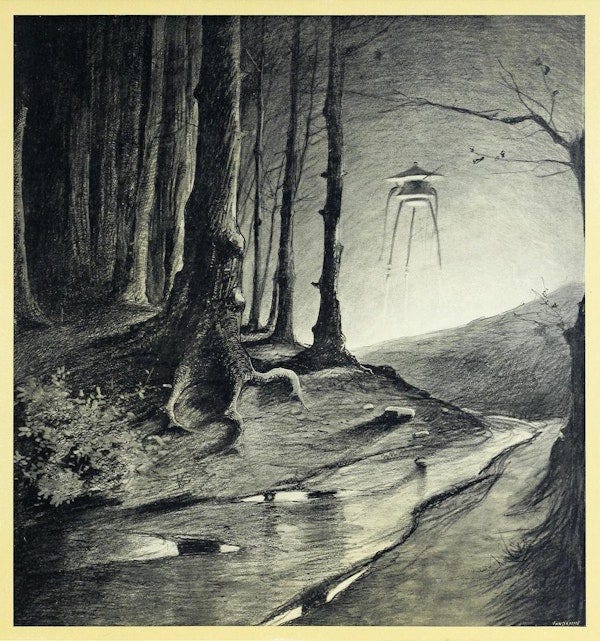

H.G. Wells’s novel The War of the Worlds is a UFO ur-text. Its first few chapters depict how a society would wake up to a disclosure-level event slowly and incrementally. It takes several days, even with constant news coverage, for the fictionalized citizens of southern England to realize what is going on. At every stage of the Martians’ arrival--the flashes observed on Mars, the shooting stars, the cylinder crashing in the pit, and the emergence of the cylinder’s occupants--people are either unaware or have differing interpretations of these events. “Even the daily papers woke up to the disturbances at last, and popular notes appeared here, there, and everywhere concerning the volcanoes upon Mars,” the novel’s narrator explains. “The seriocomic periodical Punch, I remember, made a happy use of it in the political cartoon. …It seems to me now almost incredibly wonderful that, with that swift fate hanging over us, men could go about their petty concerns as they did…. For my own part, I was much occupied in learning to ride the bicycle…”

The petty concerns of daily life have a powerful inertia. They are not pushed aside easily, and when they are, not for very long. They rush back in, as in Wells’s novel, even after much of England was laid to waste. Petty concerns are the life force of fiction, so fiction about UFOs, disclosure in particular, is a space to explore how these two powerful forces shift the orbit of the other.

Stanley Kubrick famously called up Loyds of London to procure alien insurance in case the UFOs landed before the premier of 2001: A Space Odyssey, thus crippling his box office prospects. That didn’t happen, but it will eventually happen to somebody’s movie. In my short story Four Conversations, I explore the devastating impact this scenario will have on not only one up-and-coming director’s career but how all of Hollywood tells its stories.

In Bucket of Piss and Ubuntu I explore the political side of the equation. How likely are leaders and policy makers to sideline their own power and long-fought-for policy goals simply because the UFOs show up? The answer that emerges is not easily and not very much. Which leads me to think this might be one reason why disclosure has not happened already. The psycho-social barrier to letting something utterly new usher out the old way of doing things is apparently very high.

Something utterly new. An old world ending. All of this is by definition hard to imagine. But that’s what fiction is for.

Centering the human

It’s easy to become preoccupied with the nuts-and-bolts of UFOs, their physics (or metaphysics, or temporal mechanics, etc.). It’s easy to get lost in the motives and mindsets of the extraterrestrials. But despite the apparent power of these beings and their technology, humans have been and will remain the most important players in this story. It’s our planet after all (unless, unless).

All fiction is about humans, even if there are no humans in the story. Monsters and fairies and gods and aliens are all avatars of humanity. And when an actual alien finally shows up, we will finally find out how they compare in reality to what we have long imagined them to be--a wonderful, once-in-a-species’s lifetime test of the power as well as the limitations of the human imagination.

All fiction is about humans because its wellspring is human experience. Refracting the UFO question through fiction humanizes every aspect of it.

Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (yes, I appropriated the title) is a sprawling story about humanity emigrating from their ruined planet to Mars. The Martians are beside the point, if they even show up at all (read it for yourself). Bradbury was much more interested in what we had done to the planet that necessitated our leaving it, how it would impact society and human nature if we could simply leap off the Earth in rockets and settle on an alien world. This is after all why most writers of science-fiction bother to dwell on these strange ideas—as a pretext for unmasking the strangeness that is in us.

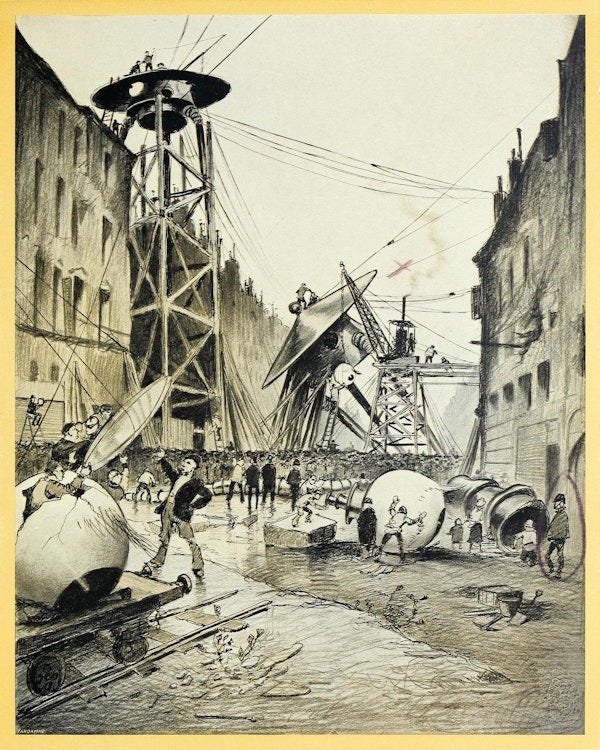

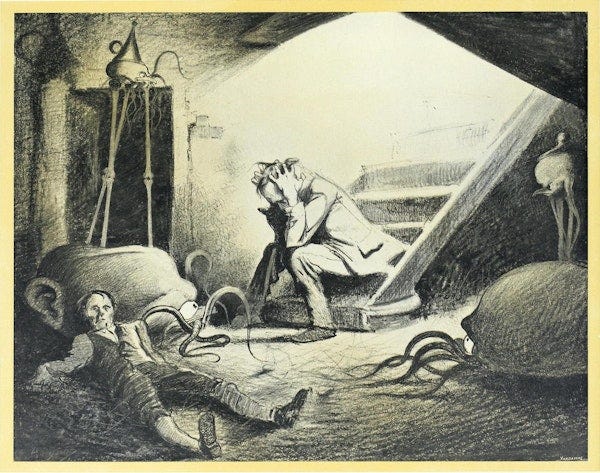

The Martians in The War of the Worlds are a mere plot device, and the famous twist ending is merely an easy means of flushing them out of the story once they had served their purpose. Wells was more interested in the seething masses of humanity set to motion by the Martians’ heat rays. The Martians are nothing more than gray blobs on the page and in my memory, but I will never forget the prophetic horror, the bone-crunching chaos of the mass exodus of London’s entire population. Nor will I forget the artilleryman we spend many pages with just before the novel’s climax. This soldier conscripts the narrator into his scheme to tunnel beneath London and start a subterranean civilization for survivors, but only for “able-bodied, clean-minded men.” Page after page, Wells explicates this character’s theories, which amount to authoritarianism motivated by disgust at the decadence of modern society. “All those damn little clerks” and other weaklings who “haven’t any spirit in them--no proud dreams and no proud lusts,” they won’t be allowed into the tunnels “for the sake of the breed.” Chillingly he adds, “They ought to be willing to die. It’s a sort of disloyalty, after all, to live and taint the race.” He’s actually quite satisfied the world is ending. The narrator is seduced by this vision at first, until he realizes it’s all blather, as the soldier keeps putting off digging and just wants to play cards and drink looted champagne. This character is stranger than the aliens, but absolutely true to life.

Fiction reminds us--warns us--that when the aliens arrive they will surface some extremely potent emotions and ideas in the hearts and minds of our fellow human beings.

It seems this has already happened, what may be the greatest untold story of the 20th century.

Since the main theme of The UFO Chronicles is disclosure, my characters are interested in why we keep secrets, how secrets are maintained, and why we can be more comfortable living a lie rather than accepting the truth. In Four Conversations I go back to 1948, a time when UFO secrecy started to become institutionalized. I try to capture what it felt like to be the first humans to come across a landed UFO in the desert, to walk across its surface, to tap its metal skin with a fire pole. What must it have been like to be the first people to experience the dawning realization of what the UFOs are, and then decide to lie about it.

In Constituent Services, I explore the motivations of a present-day intelligence agent who feels perfectly justified feeding disinformation to a national security reporter that will keep the public in the dark about a recent UFO event. We have to empathize with people like this if we are to understand how we got here, and fiction is an empathy engine.

Clarifying the stakes

None of that is to suggest that we let anyone off the hook. Writers use fiction to hold ourselves to account, to speak truth to power, to stand athwart history screaming stop. Fiction is an excellent way to layer a moral dimension onto the UFO question.

One of my characters is an elderly astronomer, so naturally she’s a practiced UFO debunker, a former SETI director no less. Faced with the reality of UFOs, her worldview crumbles. She feels lost and confused, but this quickly cuddles into rage. She asks a friend, “How could they do this to us? These men in Washington. It’s a crime. Unforgivable. Evil.” To which her friend replies, “They’re going to dazzle us with bullshit until we forget about that part.”

Morality balanced by a clear-eyed view of humanity and history, elevated by empathy and a bit of humor. These are the tools that fiction offers us as we try to make sense of UFOs, how we got here, and what is yet to come.

The UFO Chronicles: District of Columbia is available on Amazon or can be ordered from your local book store.

The Illustrations in this post are from Henrique Alvim Corrêa, who illustrated the 1906 edition of The War of the Worlds.